Regularization from Scratch - Dropout

The goal of this tutorial is to explore dropout in detail.

Prerequisites:

- Basic understanding of neural networks

- Basic PyTorch

Neural networks containing multiple non-linear hidden layers are universal approximators capable of learning very complicated relationships between inputs and outputs. This makes them extremely flexible and very powerful machine learning systems as we saw in the last post. But this flexibility can lead to overfitting, a common problem in neural networks. Large deep learning models often perform far better on training data than on validation data.

Let’s try to see that in practice. We will start by creating synthetic data as we did previously.

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

%matplotlib inline

# Import libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import torch

# The parameters of neural networks are initialized at random

# By setting a seed we should get the same initial weights every time

torch.manual_seed(42)

torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True

torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark = False

Here we are creating an Input data with 100 dimensions and 10,000 data points randomly generated from \(U(-1, 1]\). Let’s denote the dimensions of the Input vectors as \(x_{0}, x_{1}, \dots x_{99}\).

Input = 2*torch.rand(10000, 100)-1

Experiment 1 - High Dimensional Data with Extra Variables and Random Noise

We will create a Target vector from the input using the following relation:

\[ Target = f(x_{0}, x_{1}, \dots x_{99}) = x_{0}^{0} - x_{1} + x_{2}^{2} - x_{3} \dots + x_{46}^{46} - x_{47} + x_{48}^{48} - x_{49} + \epsilon \] \[ \text{where } \epsilon \text{ is random noise} \]

There is no reason for choosing this particular relation between Input and Target. We are trying to create a high-dimensional regression problem with non-linear relationship between the Input and Target vectors. Though the Input has 100 dimensions/variables, note that the relationship is dependent on only 50 variables. In practice, we will always have extra variables and noise in our data.

Target = torch.zeros(10000)

for i in range(50):

if i%2 == 0:

Temp = Input[:, i].pow(i)

Target += Temp

else:

Temp = Input[:, i]

Target -= Temp

# Add Random Noise

Noise = 0.5*torch.randn_like(Target)

Target += Noise

print('-'*20, 'Output Cell', '-'*20, '\n')

#Target Dimension

print(Target.shape)

#Reshape the target variables to appropriate dimension

Target = Target.view(10000, 1)

#New Target Dimension

print(Target.shape)

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

torch.Size([10000])

torch.Size([10000, 1])

We will use the first 5,000 elements for training our Neural Network and the remaining 5,000 elements for validation. Let’s create the DataLoader using our Input and Target.

from torch.utils.data import TensorDataset, DataLoader

Train_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[:5000], Target[:5000])

Validation_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[5000:], Target[5000:])

batch_size = 1000

Train_DataLoader = DataLoader(Train_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=True)

Validation_DataLoader = DataLoader(Validation_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size*5)

The objective is to create a Neural Network that can identify this non-linear high dimensional relationship.

Let’s create a neural network with 2 Hidden Layers and 100 units in each hidden layer and train it for 1000 epochs.

# Define Neural Network

class NeuralNetwork(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, Input_Size=100):

super(NeuralNetwork, self).__init__()

self.HiddenLayer_1 = torch.nn.Sequential(torch.nn.Linear(Input_Size, 100), torch.nn.ReLU())

self.HiddenLayer_2 = torch.nn.Sequential(torch.nn.Linear(100, 100), torch.nn.ReLU())

self.OutputLayer = torch.nn.Linear(100, 1)

def forward(self, Input):

Output = self.HiddenLayer_1(Input)

Output = self.HiddenLayer_2(Output)

Output = self.OutputLayer(Output)

return Output

# Loss Function - Cross Entropy Loss

Loss_Function = torch.nn.MSELoss()

def Training(Model, Train_DataLoader, Validation_DataLoader, learning_rate = 0.01, epochs = 1000):

print('-'*20, 'Output Cell', '-'*20, '\n')

# Optimizer - Stochastic Gradient Descent

Optimizer = torch.optim.SGD(Model.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

for epoch in range(epochs):

Model.train()

for X, Y in Train_DataLoader:

# Forward Pass

Predicted = Model(X)

# Compute Loss

Loss = Loss_Function(Predicted, Y)

# Backward Pass

Loss.backward()

Optimizer.step()

Optimizer.zero_grad()

# Calculate Validation Loss

if epoch%100 == 0:

Model.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

Validation_Loss = sum(Loss_Function(Model(X), Y) for X, Y in Validation_DataLoader)

Validation_Loss = Validation_Loss/len(Validation_DataLoader)

print('Epoch: {}. Train Loss: {}. Validation Loss: {}'.format(epoch, Loss, Validation_Loss))

Note that we put the training part of the code in a function. This will make experimentation easier. We just need to run 2 lines of code.

%%time

# Instantiate Model

Model = NeuralNetwork(Input_Size=100)

# Train the Model

Training(Model, Train_DataLoader, Validation_DataLoader, learning_rate = 0.01, epochs = 1000)

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

Epoch: 0. Train Loss: 14.482518196105957. Validation Loss: 13.808280944824219

Epoch: 100. Train Loss: 0.694995105266571. Validation Loss: 0.9867028594017029

Epoch: 200. Train Loss: 0.5789515376091003. Validation Loss: 0.9881474375724792

Epoch: 300. Train Loss: 0.39037877321243286. Validation Loss: 1.035902500152588

Epoch: 400. Train Loss: 0.2847561836242676. Validation Loss: 1.0960569381713867

Epoch: 500. Train Loss: 0.21917188167572021. Validation Loss: 1.1488596200942993

Epoch: 600. Train Loss: 0.1831873208284378. Validation Loss: 1.2025138139724731

Epoch: 700. Train Loss: 0.12253811210393906. Validation Loss: 1.2555932998657227

Epoch: 800. Train Loss: 0.09219234436750412. Validation Loss: 1.3032523393630981

Epoch: 900. Train Loss: 0.07254666090011597. Validation Loss: 1.34823739528656

CPU times: user 54.8 s, sys: 736 ms, total: 55.6 s

Wall time: 56 s

Let’s breakdown the output into 2 key points -

- Our network was able to identify the non-linear high dimensional relationship between Input and Output for training data with MSE ~ 0.07.

- The MSE for the validation dataset initially decreased to ~ 0.98 and then started to increase as we continued training never decreasing again.

This is a clear case of overfitting.

Our network overfitted on a data where the validation data is coming from the exact same distribution. One reason for overfitting could be that our model learned relations that were not present between Input and Target. It might be using the variables that were not part of the relationship: \(x_{50}, x_{51}, \dots x_{99}\) (the Target was created using \(x_{0}, x_{1}, \dots x_{49}\)). Another reason could be that our model tried to learn the random noise present in our data.

Experiment 2 - High Dimensional Data without Extra Variables or Random Noise

What if we didn’t have any noise in the data? And no extra variables? In practice, this will be nearly impossible to achieve. But for the sake of experimentation let’s do that anyway.

Let’s recreate the target variable using the following:

\[ Target = f(x_{0}, x_{1}, \dots x_{99}) = x_{0}^{0} - x_{1} + x_{2}^{2} - x_{3} \dots + x_{96}^{96} - x_{97} + x_{98}^{98} - x_{99} \]

Target = torch.zeros(10000)

for i in range(100):

if i%2 == 0:

Temp = Input[:, i].pow(i)

Target += Temp

else:

Temp = Input[:, i]

Target -= Temp

#Reshape the target variables to appropriate dimension

Target = Target.view(10000, 1)

Train_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[:5000], Target[:5000])

Validation_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[5000:], Target[5000:])

batch_size = 1000

Train_DataLoader = DataLoader(Train_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=True)

Validation_DataLoader = DataLoader(Validation_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size*5)

%%time

# Instantiate Model

Model = NeuralNetwork(Input_Size=100)

# Train the Model

Training(Model, Train_DataLoader, Validation_DataLoader, learning_rate = 0.01, epochs = 1000)

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

Epoch: 0. Train Loss: 22.0751895904541. Validation Loss: 22.568008422851562

Epoch: 100. Train Loss: 0.6760014891624451. Validation Loss: 0.9361695051193237

Epoch: 200. Train Loss: 0.45045265555381775. Validation Loss: 0.9307345747947693

Epoch: 300. Train Loss: 0.33922550082206726. Validation Loss: 0.9536352753639221

Epoch: 400. Train Loss: 0.22653190791606903. Validation Loss: 0.9807875156402588

Epoch: 500. Train Loss: 0.17093497514724731. Validation Loss: 1.0150508880615234

Epoch: 600. Train Loss: 0.12273935228586197. Validation Loss: 1.044995665550232

Epoch: 700. Train Loss: 0.09949737787246704. Validation Loss: 1.0784345865249634

Epoch: 800. Train Loss: 0.08115856349468231. Validation Loss: 1.1115176677703857

Epoch: 900. Train Loss: 0.06317076832056046. Validation Loss: 1.1423213481903076

CPU times: user 55.1 s, sys: 647 ms, total: 55.7 s

Wall time: 56 s

Again let’s breakdown the results into 2 key points -

- Our network was able to identify the non-linear high dimensional relationship between Input and Output for training data with MSE ~ 0.06

- The MSE for validation dataset initially decreased to ~ 0.93 and then started to increase as we continued training

Even in the absence of any statistical noise, our model can overfit. As the dimension of the input increases, the flexibility of our model increases. Higher dimension size means more parameters that make the model’s function selection range wider making it more prone to overfitting as there will be many different functions that can model the training set almost perfectly.

There are various ways to address this problem of overfitting. We can reduce the input dimension, increase training data, or use weight penalties of various kinds such as \(L1\) and \(L2\) regularization. In this post, we will be looking at one of the key techniques for reducing overfitting in neural networks - Dropout.

Dropout

In 2014, Srivastava et al. published a paper titled Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting revolutionizing the field of deep learning. In their paper, they introduced the idea of randomly dropping units from the neural network during training. They explained that dropout prevents overfitting and provides a way of combining different neural network architectures efficiently.

Ensembling multiple models is a good way to reduce overfitting and nearly always improves performance. So, we can train a large number of neural networks and average their predictions to get better results. However, this can be very challenging with bigger networks. Training a large neural network is computationally expensive and training multiple models might not be feasible. Ensembling is generally more helpful when the models are not correlated i.e, they should be different from each other. To achieve that the neural networks would need to be of different architectures and trained on different data. This also can be very challenging as we will need to tune every architecture separately. Also, there may not be enough data available to train different networks on different subsets of the data.

Dropout is a technique that provides a way of combining many different neural network architectures efficiently.

Dropout during Training

Dropout means randomly switching off some hidden units in a neural network while training. During a mini-batch, units are randomly removed from the network, along with all their incoming and outgoing connections resulting in a thinned network. Each unit is retained with a fixed probability \(p\) independent of other units. This means that the probability of a unit being dropped in a mini-batch will be \(1-p\).

Since neural networks are a series of affine transformations and non-linearities, a unit can be dropped by multiplying its output value by zero. Thus, dropout can be implemented by multiplying outputs of activations by Bernoulli distributed random variables which take the value 1 with probability \(p\) and 0 otherwise. \(p\) is a hyperparameter fixed before training.

Commonly \(p=0.5\) is used for hidden units and \(p=0.8\) for input units.

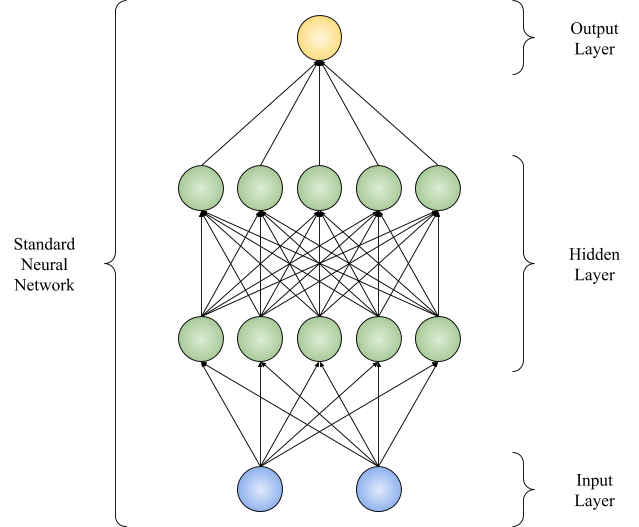

Let’s look at an example of a neural network with 2 hidden layers Fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Neural Network with 2 input units and 5 hidden units in 2 hidden layers

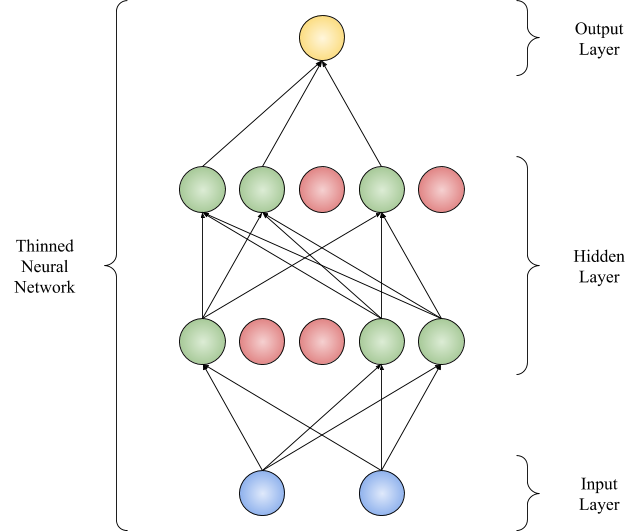

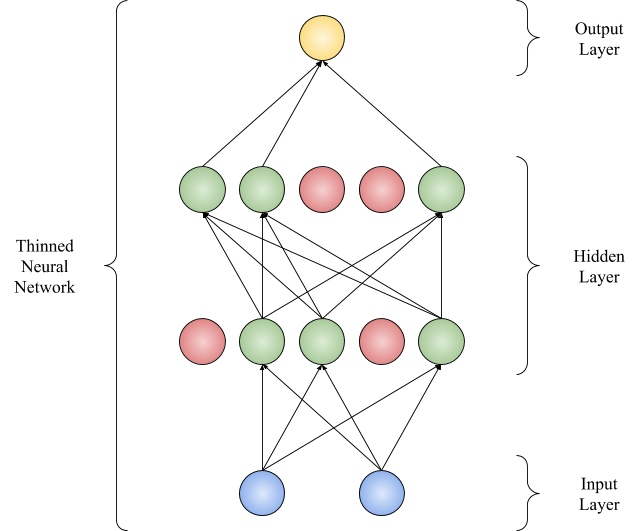

Let’s apply dropout to its hidden layers with \(p=0.6\). \(p\) is the ‘keep probability’. This makes the probability of a hidden unit being dropped equal \(1-p=0.4\). Thus with every forward pass, 40% of units will be switched off randomly. This will vary with every mini-batch in every epoch: Fig. 2 and Fig. 3.

\(2^{n}\) thinned neural networks can be generated from a neural network with \(n\) units. So training a neural network with dropout can be seen as training exponentially large number of neural networks from the collection of \(2^{n}\) thinned networks where the weights are shared between them.

Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 illustrate how this network might look like during forward propagation.

Fig. 2: Neural Network with 40% hidden units dropped

Different subnetworks will be generated with every forward pass. The dropped units are colored in red.

Fig. 3: Neural Network with 40% hidden units dropped

Since this network has 10 hidden units, \(2^{10}\) different thinned networks are possible.

Dropout in Practice

Let’s create the neural network shown in Fig. 1 and apply dropout to it.

# Mini Batch of 10 elements

# Input with 2 dimensions

X = torch.rand(10, 2)

# Weight for Hidden Layer 1 with 5 units

W1 = torch.rand(2, 5)

# Bias for Hidden Layer 1 with 5 units

B1 = torch.rand(5)

# Weight for Hidden Layer 2 with 5 units

W2 = torch.rand(5, 5)

# Bias for Hidden Layer 2 with 5 units

B2 = torch.rand(5)

# Weight for Output Layer

W3 = torch.rand(5, 1)

# Bias for Output Layer

B3 = torch.rand(1)

Let’s assume the activation function is \(ReLU\) for our network. If we don’t apply dropout, we will have a normal forward pass for this mini-batch.

# Mutiply Input by W1 and add bias B1

H1 = X@W1 + B1

# Apply ReLU activation

H1.clamp_(0)

# H1 is the output from Hidden Layer 1

# Mutiply H1 by W2 and add bias B2

H2 = H1@W2 + B2

# Apply ReLU activation

H2.clamp_(0)

# H2 is the output from Hidden Layer 2

# Mutiply H2 by W3 and add bias B3

Out = H2@W3 + B3

To apply dropout we will create a binary vector, commonly called as binary mask, where \(1\)’s will represent the units to keep and \(0\)’s will represent the units to drop.

print('-'*20, 'Output Cell', '-'*20, '\n')

# Mask for keeping units with probability p

# Mask for dropping units with probability 1-p

mask = torch.zeros(1, 5).bernoulli_(0.6)

mask

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

tensor([[1., 0., 1., 0., 1.]])

Let’s look at the output of Hidden Layer 1 without dropout. The output vector of this layer will have 5 elements; 1 from every hidden unit.

print('-'*20, 'Output Cell', '-'*20, '\n')

# Output of Hidden Layer 1

H1

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

tensor([[1.4571, 0.9301, 1.5057, 1.0187, 1.0740],

[2.0775, 1.2849, 1.8956, 1.4305, 1.3876],

[1.3839, 0.8882, 1.4594, 0.9700, 1.0363],

[1.1605, 0.7488, 1.2952, 0.8139, 0.8683],

[1.2070, 0.7238, 1.2188, 0.8101, 0.6482],

[1.2837, 0.7614, 1.2542, 0.8569, 0.6575],

[1.9915, 1.2499, 1.8704, 1.3829, 1.4107],

[1.0826, 0.7468, 1.3334, 0.7908, 1.0303],

[0.8492, 0.5682, 1.0942, 0.6055, 0.6988],

[1.1232, 0.7963, 1.4127, 0.8354, 1.1750]])

To apply the dropout mask, we do an element-wise product. We can look at the result and confirm that unit 2 and unit 4 have been turned off.

print('-'*20, 'Output Cell', '-'*20, '\n')

mask*H1

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

tensor([[1.4571, 0.0000, 1.5057, 0.0000, 1.0740],

[2.0775, 0.0000, 1.8956, 0.0000, 1.3876],

[1.3839, 0.0000, 1.4594, 0.0000, 1.0363],

[1.1605, 0.0000, 1.2952, 0.0000, 0.8683],

[1.2070, 0.0000, 1.2188, 0.0000, 0.6482],

[1.2837, 0.0000, 1.2542, 0.0000, 0.6575],

[1.9915, 0.0000, 1.8704, 0.0000, 1.4107],

[1.0826, 0.0000, 1.3334, 0.0000, 1.0303],

[0.8492, 0.0000, 1.0942, 0.0000, 0.6988],

[1.1232, 0.0000, 1.4127, 0.0000, 1.1750]])

Putting all the code together to implement dropout from scratch!

# Mutiply Input by W1 and add bias B1

H1 = X@W1 + B1

# Apply ReLU activation

H1.clamp_(0)

# Apply dropout

mask = torch.zeros(1, 5).bernoulli_(0.6)

H1 = mask * H1

# H1 is the output from Hidden Layer 1

# Mutiply H1 by W2 and add bias B2

H2 = H1@W2 + B2

# Apply ReLU activation

H2.clamp_(0)

# Apply dropout

mask = torch.zeros(1, 5).bernoulli_(0.6)

H2 = mask * H2

# H2 is the output from Hidden Layer 2

# Mutiply H2 by W3 and add bias B3

Out = H2@W3 + B3

Inference

One of the most common method of combining multiple models is to take arithmetic mean of the predictions from each model. But in dropout, there can be exponentially many thinned models and it becomes unfeasible to store and average predictions from all the models.

The predictions of the combined models can be approximated by averaging together the output from a few thinned networks. 10–20 such subnetworks are often sufficient to obtain good performance.

Another good approximation can be achieved by taking the geometric mean of the predictions. The arithmetic mean and geometric mean often perform comparably when ensembling. More details can be found in this paper.

Note that the geometric mean of multiple predictions might not be a probability distribution. Therefore, a condition is placed that none of the submodels can assign a probability of 0 to any event. Also, the resulting distribution is normalized.

Arithmetic Mean \[ p_{ensemble} = \sum_{\mu}^{}p(\mu)p(y|x, \mu) \]

Geometric Mean \[ p_{ensemble} = \bigg(\prod_{\mu}^{}p(y|x, \mu)\bigg)^{\frac{1}{2^{d}}} \]

\(where\)

\(\mu\) represents the mask vector

\(p(\mu)\) is the probability distribution used to sample \(\mu\) during training

\(p(y|x, \mu)\) prediction of thinned network

\(d\) is the number of units that may be dropped

Inference for dropout is achieved by approximating the geometric mean. If \(p\) is the probability of a unit being retained during training, then the outgoing weights of that unit are multiplied by \(p\) at test time. The idea is to keep the expected output value from the unit same during training and test time. This approximates the geometric mean of predictions of the entire ensemble. Empirically training a network with dropout and using this approximate averaging method at test time improves generalization and reduces overfitting and can work as well as Monte-Carlo Model Averaging.

Let’s implement the inference part of dropout along with the training part.

############# TRAINING #############

# Mutiply Input by W1 and add bias B1

H1 = X@W1 + B1

# Apply ReLU activation

H1.clamp_(0)

# Apply dropout

mask = torch.zeros(1, 5).bernoulli_(0.6)

H1 = mask * H1

# H1 is the output from Hidden Layer 1

# Mutiply H1 by W2 and add bias B2

H2 = H1@W2 + B2

# Apply ReLU activation

H2.clamp_(0)

# Apply dropout

mask = torch.zeros(1, 5).bernoulli_(0.6)

H2 = mask * H2

# H2 is the output from Hidden Layer 2

# Mutiply H2 by W3 and add bias B3

Out = H2@W3 + B3

############# INFERENCE #############

# Mutiply Input by W1 and add bias B1

H1 = X@W1 + B1

# Apply ReLU activation

H1.clamp_(0)

# Scaling the output of Hidden Layer 1

H1 = H1*0.6

# H1 is the output from Hidden Layer 1

# Mutiply H1 by W2 and add bias B2

H2 = H1@W2 + B2

# Apply ReLU activation

H2.clamp_(0)

# Scaling the output of Hidden Layer 2

H2 = H2*0.6

# H2 is the output from Hidden Layer 2

# Mutiply H2 by W3 and add bias B3

Out = H2@W3 + B3

Inverted Dropout

Till now we have applied dropout as per the dropout paper. However, most of the libraries, like PyTorch, implement ‘Inverted Dropout’.

In invereted dropout, the scaling is applied during training. Inverted dropout randomly retains some activations with probability \(p\) similar to traditional dropout. Then scaling is done by multiplying the output of retained units \(1/p\). Since scaling is done during training, no changes are required during evaluation.

Let’s apply scaling during training to implement inverted dropout.

############# TRAINING #############

# Mutiply Input by W1 and add bias B1

H1 = X@W1 + B1

# Apply ReLU activation

H1.clamp_(0)

# Apply dropout

mask = torch.zeros(1, 5).bernoulli_(0.6)

H1 = mask * H1

# Scaling the output of Hidden Layer 1

H1 = H1/0.6

# H1 is the output from Hidden Layer 1

# Mutiply H1 by W2 and add bias B2

H2 = H1@W2 + B2

# Apply ReLU activation

H2.clamp_(0)

# Apply dropout

mask = torch.zeros(1, 5).bernoulli_(0.6)

H2 = mask * H2

# Scaling the output of Hidden Layer 2

H2 = H2/0.6

# H2 is the output from Hidden Layer 2

# Mutiply H2 by W3 and add bias B3

Out = H2@W3 + B3

############# INFERENCE #############

# Mutiply Input by W1 and add bias B1

H1 = X@W1 + B1

# Apply ReLU activation

# No Scaling Required

H1.clamp_(0)

# H1 is the output from Hidden Layer 1

# Mutiply H1 by W2 and add bias B2

H2 = H1@W2 + B2

# Apply ReLU activation

# No Scaling Required

H2.clamp_(0)

# H2 is the output from Hidden Layer 2

# Mutiply H2 by W3 and add bias B3

Out = H2@W3 + B3

Experiment 1 - Revisited With Dropout

Let’s try to implement dropout for Experiment 1 to reduce the overfitting. Since we didn’t change Input and Noise tensors, we can recreate the exact same target.

Target = torch.zeros(10000)

for i in range(50):

if i%2 == 0:

Temp = Input[:, i].pow(i)

Target += Temp

else:

Temp = Input[:, i]

Target -= Temp

# Add Random Noise

Target += Noise

#Reshape the target variables to appropriate dimension

Target = Target.view(10000, 1)

Train_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[:5000], Target[:5000])

Validation_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[5000:], Target[5000:])

batch_size = 1000

Train_DataLoader = DataLoader(Train_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=True)

Validation_DataLoader = DataLoader(Validation_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size*5)

We will implement dropout in our NeuralNetwork class.

There are 2 key points we need to note in the code below:

- self.training: While in training mode, PyTorch sets self.training to True and in evaluation mode, it is set as false. Since the behaviour of dropout is different for training and inference, model.train() and model.eval() should be used to get the correct results.

- Till now we have considered \(p\) as the keep probability and \(1-p\) as the probability of dropout. In our code, we will consider \(p\) as the probability of dropout and \(1-p\) as the probability of survival and change the scaling formula accordingly.

# Define Neural Network

class NeuralNetwork(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, Input_Size=100, Dropout=0.5):

super(NeuralNetwork, self).__init__()

self.HiddenLayer_1 = torch.nn.Sequential(torch.nn.Linear(Input_Size, 100), torch.nn.ReLU())

self.HiddenLayer_2 = torch.nn.Sequential(torch.nn.Linear(100, 100), torch.nn.ReLU())

self.OutputLayer = torch.nn.Linear(100, 1)

self.Dropout = Dropout

def forward(self, Input):

Output = self.HiddenLayer_1(Input)

# Use dropout only when training the model

if self.training:

DropoutMask = torch.zeros(1, 100).bernoulli_(1-self.Dropout)

Output = (Output*DropoutMask)/(1-self.Dropout) #Scaling with 1-p

Output = self.HiddenLayer_2(Output)

# Use dropout only when training the model

if self.training:

DropoutMask = torch.zeros(1, 100).bernoulli_(1-self.Dropout)

Output = (Output*DropoutMask)/(1-self.Dropout) #Scaling with 1-p

Output = self.OutputLayer(Output)

return Output

# Loss Function - Cross Entropy Loss

Loss_Function = torch.nn.MSELoss()

def Training(Model, Train_DataLoader, Validation_DataLoader, learning_rate = 0.01, epochs = 1000):

print('-'*20, 'Output Cell', '-'*20, '\n')

# Optimizer - Stochastic Gradient Descent

Optimizer = torch.optim.SGD(Model.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

for epoch in range(epochs):

Model.train()

for X, Y in Train_DataLoader:

# Forward Pass

Predicted = Model(X)

# Compute Loss

Loss = Loss_Function(Predicted, Y)

# Backward Pass

Loss.backward()

Optimizer.step()

Optimizer.zero_grad()

# Calculate Validation Loss

if epoch%100 == 0:

Model.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

Validation_Loss = sum(Loss_Function(Model(X), Y) for X, Y in Validation_DataLoader)

Validation_Loss = Validation_Loss/len(Validation_DataLoader)

print('Epoch: {}. Train Loss: {}. Validation Loss: {}'.format(epoch, Loss, Validation_Loss))

%%time

# Instantiate Model

Model = NeuralNetwork(Input_Size=100, Dropout=0.5)

# Train the Model

Training(Model, Train_DataLoader, Validation_DataLoader, learning_rate = 0.01, epochs = 1000)

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

Epoch: 0. Train Loss: 13.633894920349121. Validation Loss: 12.919963836669922

Epoch: 100. Train Loss: 2.7887604236602783. Validation Loss: 1.3544188737869263

Epoch: 200. Train Loss: 1.0066168308258057. Validation Loss: 1.0069533586502075

Epoch: 300. Train Loss: 1.1311012506484985. Validation Loss: 0.9397183656692505

Epoch: 400. Train Loss: 0.9387773871421814. Validation Loss: 0.9175894260406494

Epoch: 500. Train Loss: 0.7152908444404602. Validation Loss: 0.9644955992698669

Epoch: 600. Train Loss: 0.6427285671234131. Validation Loss: 0.9647810459136963

Epoch: 700. Train Loss: 1.0787990093231201. Validation Loss: 0.9440218806266785

Epoch: 800. Train Loss: 0.7154536843299866. Validation Loss: 0.9039661884307861

Epoch: 900. Train Loss: 0.8444961905479431. Validation Loss: 0.9420482516288757

CPU times: user 59.4 s, sys: 1.18 s, total: 1min

Wall time: 1min

Compare the current results with the previous results for the same experiment. By applying dropout, we improved validation loss from 0.98 to 0.90. The gap between MSE for train and validation is also reduced.

Dropout significantly reduced overfitting for Experiment 1 and improved generalization, resulting in better performance on the validation set.

Experiment 2 - Revisited With Dropout

Let’s implement dropout for Experiment 2.

Target = torch.zeros(10000)

for i in range(100):

if i%2 == 0:

Temp = Input[:, i].pow(i)

Target += Temp

else:

Temp = Input[:, i]

Target -= Temp

#Reshape the target variables to appropriate dimension

Target = Target.view(10000, 1)

Train_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[:5000], Target[:5000])

Validation_Dataset = TensorDataset(Input[5000:], Target[5000:])

batch_size = 1000

Train_DataLoader = DataLoader(Train_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=True)

Validation_DataLoader = DataLoader(Validation_Dataset, batch_size=batch_size*5)

PyTorch’s torch.nn.Module provides a dropout class that can be used directly. It automatically handles mask creation and scaling. The probability argument in torch.nn.Dropout is the probability of units being dropped out.

# Define Neural Network

class NeuralNetwork(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, Input_Size=100, Dropout=0.5):

super(NeuralNetwork, self).__init__()

self.HiddenLayer_1 = torch.nn.Sequential(torch.nn.Linear(Input_Size, 100), torch.nn.ReLU(), torch.nn.Dropout(Dropout))

self.HiddenLayer_2 = torch.nn.Sequential(torch.nn.Linear(100, 100), torch.nn.ReLU(), torch.nn.Dropout(Dropout))

self.OutputLayer = torch.nn.Linear(100, 1)

def forward(self, Input):

Output = self.HiddenLayer_1(Input)

Output = self.HiddenLayer_2(Output)

Output = self.OutputLayer(Output)

return Output

# Loss Function - Cross Entropy Loss

Loss_Function = torch.nn.MSELoss()

def Training(Model, Train_DataLoader, Validation_DataLoader, learning_rate = 0.01, epochs = 1000):

print('-'*20, 'Output Cell', '-'*20, '\n')

# Optimizer - Stochastic Gradient Descent

Optimizer = torch.optim.SGD(Model.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

for epoch in range(epochs):

Model.train()

for X, Y in Train_DataLoader:

# Forward Pass

Predicted = Model(X)

# Compute Loss

Loss = Loss_Function(Predicted, Y)

# Backward Pass

Loss.backward()

Optimizer.step()

Optimizer.zero_grad()

# Calculate Validation Loss

if epoch%100 == 0:

Model.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

Validation_Loss = sum(Loss_Function(Model(X), Y) for X, Y in Validation_DataLoader)

Validation_Loss = Validation_Loss/len(Validation_DataLoader)

print('Epoch: {}. Train Loss: {}. Validation Loss: {}'.format(epoch, Loss, Validation_Loss))

%%time

# Instantiate Model

Model = NeuralNetwork(Input_Size=100, Dropout=0.5)

# Train the Model

Training(Model, Train_DataLoader, Validation_DataLoader, learning_rate = 0.01, epochs = 1000)

-------------------- Output Cell --------------------

Epoch: 0. Train Loss: 25.26565170288086. Validation Loss: 22.792816162109375

Epoch: 100. Train Loss: 1.9885936975479126. Validation Loss: 0.9988459944725037

Epoch: 200. Train Loss: 1.5658793449401855. Validation Loss: 0.9235767722129822

Epoch: 300. Train Loss: 1.2947447299957275. Validation Loss: 0.8972725868225098

Epoch: 400. Train Loss: 1.313409447669983. Validation Loss: 0.8803383708000183

Epoch: 500. Train Loss: 1.2465885877609253. Validation Loss: 0.878248929977417

Epoch: 600. Train Loss: 1.2394073009490967. Validation Loss: 0.8703423738479614

Epoch: 700. Train Loss: 1.0760048627853394. Validation Loss: 0.8612719774246216

Epoch: 800. Train Loss: 0.9913138747215271. Validation Loss: 0.8619877099990845

Epoch: 900. Train Loss: 0.9837628602981567. Validation Loss: 0.8579367995262146

CPU times: user 59.9 s, sys: 1.33 s, total: 1min 1s

Wall time: 1min 1s

Again we see a significant reduction in overfitting and improved performance on validation set - MSE dropped from 0.93 to 0.85. Dropout can also be combined with other forms of regularization to get further improvement.

Salient Features

Training a neural network with dropout can be seen as training multiple networks where the weights are shared between them. Since the architecture of the model changes with every mini-batch, every unit learns to perform well regardless of which other hidden units are present in the model. This makes the units robust independently that is good in many settings, thereby preventing co-adaptation. This results in better performance and improved generalization error compared to the performance obtained by ensembles of independent models. You can get more details from this paper.

Dropout can also be seen as a way of adding noise to the states of hidden units. As dropout causes destruction of some information from input, units are forced to learn other features and make use of all the knowledge about the input.

Dropout can also be modified by multiplying the activations with random variables drawn from other distributions.

Caution

We need to exercise some caution when implementing dropout in neural networks.

-

A neural network with dropout usually needs to be trained longer as the parameter updates are very noisy.

-

A larger neural network is required when applying dropout. Dropout is a regularization technique and reduces the expressiveness of neural networks. The combination of a larger network with dropout typically results in lower validation error.

Summary

Dropout is a computationally inexpensive but powerful technique for improving neural networks by reducing overfitting. Dropout trains an ensemble of multiple thinned subnetworks that can be formed by removing hidden or input units from a base network. This prevents networks from building brittle co-adaptations that do not generalize well.

In this tutorial, we explored dropout in detail and implemented it from scratch. We can now leverage this remarkably effective technique to improve the performance of neural nets in a wide variety of applications.